Do you like visiting cemeteries ? In the UK we lived very close to one and it was a popular route to take into town, with plenty of mature trees, squirrels, birds and a large wild flower patch, yellow with dandelions in the spring.

Maybe that’s why we had no problem with buying a house that overlooked a graveyard here in France. The advantages are many. No-one will be able to develop the land and build a block of flats that blocks out our light. It is locked at night and surrounded by a high wall so thieves would find it very difficult to break into our house from behind. It is also very calm. No noisy neighbours for us!

We have a little joke that we like to tell people when they visit. The family across the road have the very un-French surname of More. So we tell visitors that we are ‘entre les morts’. We have the dead – ‘les morts’ on one side and ‘Les Mores’ on the other, so we are between the dead!

We have been very surprised to find that the average French attitude is very different. People will refuse point blank to rent or buy a home next to the dead. The reticence to have tombs near to dwellings can be seen in the placement of cemeteries. In the UK the local church usually has a large patch of sacred ground round it, but this is rarely the case in France. Cemeteries are often far from the village and out of sight behind a high brick wall.

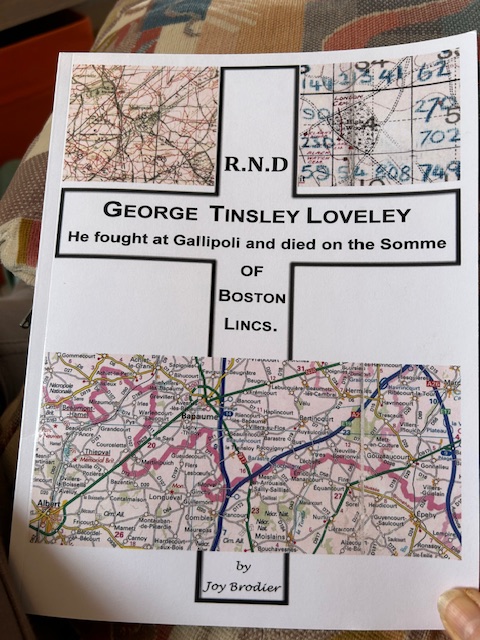

When I was researching the history of my grandfather’s brother who was killed in France in 1917 on the Somme, I set out to find the local cemetery in the village of Courcelette. My Great-uncle was killed at the age of 24 during a German advance. His body was found and his papers were sent to the British by the ‘enemy’. The family were told that he was buried in German Cemetery No 1. But now that graveyard has been lost.

I wanted to see if there were any isolated German or British soldier’s graves in the local village among those of civilians. I searched maps. I searched the village website, but there was nothing, no mention of one. I knew this could not be the case – there was one in every village.

In the end I went onto Google Earth and virtually ‘walked’ along every road out of the hamlet. Along country lane, was an unusually high, neatly trimmed, hedge. I said to my husband, ‘That is where we must look.’ We visited the area and hey presto, I had found what had not been marked on any map – the well-hidden burial ground.

If you are in France during October the cemetery is one of the places to be. At the end of the month are two weeks of half-term holidays for school children, culminating in 1st November Toussaint national holiday. Traditionally, flowers are placed on the graves for All Saints’ Day.

I must add that the right to have a grave space is often only 30 years. If the grave is left untended and neglected the local council will repossess it and re-use it! Terrible news for family history addicts. Thus, during October far more visitors than usual come to see where their loved ones are interred.

The grave must be weeded and cleaned. People arrive with buckets and cleaning materials to give the marble headstones a good scrub. Nearly everyone comes armed with a large pot of chrysanthemums. Modern intensive plant breeding means that these ‘golden flowers’ , for that is the meaning in Greek, can now be bought in all shades of yellow, red, pink, white and purply-bronze.

The view from our window becomes more and more florid as the days pass. Families come with little children in pushchairs, couples arrive, older people with mobility problems do their duty to their sadly missed defuncts.

There was an advert on British TV quite a long time ago for an Italian product. In it a young man left a bunch of chrysanthemums on the doorstep of a girl he was hoping to impress. Grandma came home, saw the flowers and burst into tears. The viewers were supposed to know that chrysanths are associated with death in most of southern Europe. Don’t ever take a bunch as a present to anyone. They will be very taken aback.

We often take a walk around at the close of the day to appreciate our own Chelsea flower show. Sometimes there are poignant flower arrangements. The Victorians were known for using ‘the language of flowers’ to transmit secret messages. Three vases of identical Chrysanthemums with a few red roses among them, surely spoke of ‘love’ separated by ‘death’?

Sadly, these hothouse-grown plants don’t last very long once the November weather takes hold. Sometimes strong winds wreak havoc, and pots are overturned and can be seen rolling around on their sides. Cold rain soon kills these tender plants.

The council gardeners come with a pick-up truck and any dead or dying ones are quickly removed. The big green bins are overflowing with discarded floral arrangements. However, rich pickings can sometimes be had by removing the nicest pots before the bin men arrive. Gardeners can never have enough recipients!

I feel a bit like the unofficial guardian. When, one evening at dusk a man staggered along the path, I was concerned. I was even more worried when neither I nor my husband, from the vantage point of our dining room table, had noticed him leave as night began to fall.

I had always wondered what would happen if someone fell among the tombs, unable to get up. I decided to go and check. I entered, but saw nothing, I continued, still nothing. Then right at the far end, I saw a body lying over a ground level memorial. I hurried towards him fearing the worst but was relieved to hear sobs and breathing. I encouraged him to get up and to come with me.

Fortunately, some younger family members soon arrived and took charge. I explained that I had seen him enter and indicated my house. Later on in the week someone knocked at my door. It was the man who had been in deep distress. He thanked me and sadly explained that the tomb was his wife’s who had committed suicide.

Cut price tombs! Every October time there are adverts in the papers for reductions in the price of memorials. I wonder what happens if you buy one. Does it get delivered and you store it in your garage until needed?

I heard of someone who wanted a marble table for his garden, but needed the help of half a dozen friends to lift it into place. I wonder if the reductions in October are attractive, we could make use of the slab as a luxurious outdoor eating surface in the mean time!

George Tinsley Loveley – ‘He fought at Gallipoli and died on the Somme.’ Available on Amazon by Joy Brodier